I’ve been familiar with chisels since childhood. I loved them as much as I loved my toys. The small chisel I stole from my brother’s kit who was a mason took up a special spot among my childhood belongings, from adorned wooden spinning tops to coloured crystal balls. I hid it in a closet of mine along with my cars, metal figures, plastic airplanes, and kites.

That chisel was both my toy and treasure. At first, I didn’t understand this attachment to a piece of steel that could penetrate and carve the surface of a stone. I wasn’t aware of the effects of that magical tool on my path and its future orientations. All I knew was that I felt a tremendous passion towards it, very similar to the attachment I had for the rest of my toys.

.jpg)

I cannot forget when the sledgehammers of Abou Youssef, Abou George, Mu’allim Hebbo and Mu’allim Abdo smashed down huge rocks. When I was small, I used to watch these quarrymen extracting building stones from my brother Mansour’s quarry. I was a boy of 10 years old or less. I would carry my books and study while watching these powerful men subtly take out a giant rock from the core of the earth. They would move away the soil around it, estimate its measurements and study its layers and strata (a stratum is the line that separates geologic layers in rocks) in order to know how to install wedges successfully. A “separation” wedge is a horizontal hole that quarrymen dig using a “cutter”; it’s a hammer with a head like that of a chisel. It pierces a rock and leaves a space for wedges to pass through horizontally or vertically to break the rock in two. The quarryman separates the rock using the huge lever. They then cut it into several chunks of different sizes and measurements, depending on the usage of each. The big ones are used for polls and sills. The medium ones for corners and lower sills of windows and doors, and the small ones for stones of wall pillars.

This process of cutting drew my attention and astonished me, especially when a quarryman carved a small hole (a groove in the stone of 5 cm-width at the most) in a chunk of the big rock using his different tools: he would start with the pick, a carving tool that resembles a big hammer, sharp on both sides; then he would finish off with the cutter. After that, the quarryman would use his heavy sledgehammer (it can weigh up to 15 kilograms) to deliver hard, balanced, precise blows all along the hole he carved. After a few seconds and no more than ten blows, the rock would break in two. The quarryman would repeat this process with the rest of the chunks so the stones became approximately the same size, measurements and thickness. What followed was the process of slimming (reducing the thickness) using a spalling hammer. The stones were then used in construction, so the quarryman would cut them, carve their edges and parallel their lines. A mason would turn these stones into normal houses or mansions with carved or ornamented spans & windows.

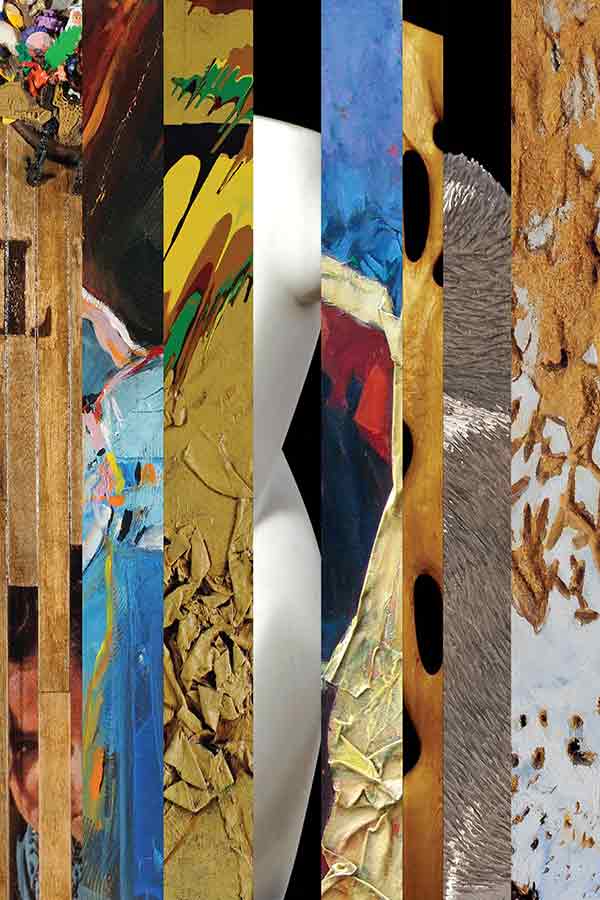

I elaborated too much on the process of extracting, smashing and building rocks to draw attention to the importance of a hard profession that became from the past. Also, to confirm my connection to rocks since my childhood and the huge impact it had on my artistic orientations later on in life. I saw the difficulty of the profession of sculpting. I witnessed it and practiced it. I told its secrets and the secrets of its rocks in all their harshness and softness, their tones and resonance, their colours and veins, their stubbornness and submission, their aspects and glow, their mobility and rigidity… to show the deep passion that I have had, since childhood, towards nature; from soil to rocks and plants; and my strong connection to all of that. Rigid substances deepened my connection with art and encouraged me to walk down that sweet bumpy path.

At the beginning, art was a naïve confused passion related to the playful nature and innocence of a child. Later on, it became a doubtless purposeful attachment nurtured from knowledge that accumulated and became crystal clear at the stage of maturity and commitment. Art became an actual cause that took over my existential consciousness. It incited me, motivated me and pushed me to walk down its paths and experience its successive, intertwined, inseparable and integrated stages, which led me to all of my accomplishments.

Playing with my primitive tools and natural materials represented my first attempts at carving. I resumed the journey and went further using all kinds of power and sculpting tools.

I got familiar with rocks, marble, wood and clay. I started seeing art from an evolved perspective. I clung to it more and more. My life became part of it; I lived as a monk in its temples. All sculptures, paintings and artistic work became hymns of the Creator longing for pure spiritual prospects. Paintings and sculptures were not just outcomes of good skill, precise work and effective methods. Sculpting was not just a struggle between the sculptor and raw rocky matter; it became an exquisite creation. High skills and advanced techniques now only complement and strengthen the beautiful work already done.

In this alluring atmosphere, my imagination takes me to other dimensions where reality and dreams become one, turning rigid substances into life-like creatures. I hold a chunk of hard rock in my hands, and it turns into a mass of soft, sticky, supple clay. Instantly, shapes and sizes flow from the imagination to settle down in the hard transforming substance through instinct and spontaneity using different tools, techniques and expertise; they become sculptures overflowed with emotions. My eyes and hands follow these emotions till the very illuminated end without caring about the obstacles an expert may face, from dust and noise to the outcry of rocks and the scattering of their solid particles into now-thick clouds of white dust, rendering vision obscure. Here, my body becomes numb and the creator inside of me wakes up and emancipates himself to create, in turn, life in a rock that has been dead for ages.

Every puncture of a chisel, every blow of a hammer or cut of a machine shake the world of a stone and wake it up from its sleep leading it to the light. Rocks dig their way out to existence granting their rigidity a whole other entity that moves in the skies of minds, tastes and feelings.

The scratches of a chisel, the cracks of a hammer, the dust and cuts of a machine, the scrabbles of a rasp, the rustling sound of glass paper and the scalpels of a surgeon save the rigid substance from disappearing into nothingness. Its lazy atoms move and throw it in the world of life and mobility.

This is how a sculpture is born; from the magic of the merciful hand, from the outcry of cutting tools, from the groan of its submissive rock. It lives on while imagining, in the open and under the light, a verse to glorify its creator.

You can read the original text in Arabic on this link.